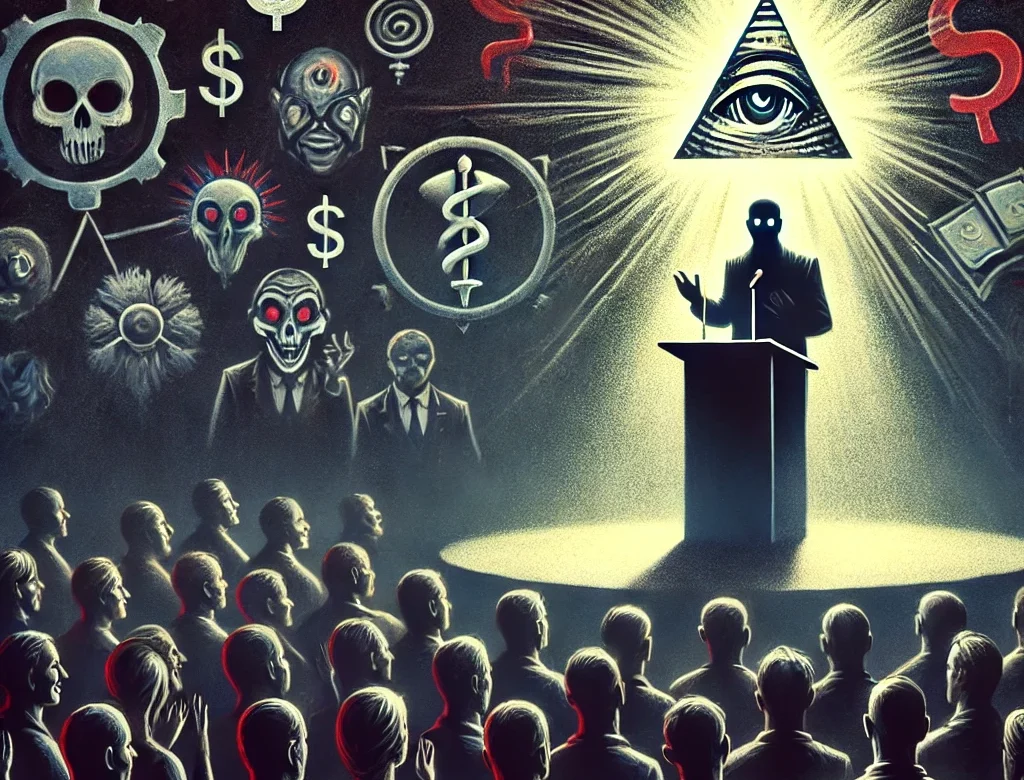

Why people support corrupt figures?

Throughout history, society has been both fascinated and repelled by figures who defy moral and ethical norms. From convicted criminals to corrupt leaders, a disturbing pattern emerges—individuals with histories of fraud, abuse, and manipulation still manage to attract loyal followers, romantic admirers, and unwavering political support. This raises a crucial question: Why are so many people drawn to figures who embody deception, cruelty, or outright criminality?

One of the most striking contemporary examples is Donald Trump, a man who has faced multiple accusations of fraud, sexual misconduct, and unethical business practices, yet commands a devoted following. Trump has been accused of sexual assault by multiple women (Kaplan, 2023), operated Trump University, a fraudulent education scheme that exploited students (U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, 2016), and misused charity funds meant for veterans, resulting in a $2 million settlement (New York Attorney General, 2019). Despite these transgressions, millions continue to idolize him, dismiss evidence, and passionately defend his actions.

Trump is not unique—from dictators to cult leaders, the allure of repugnant figures is a well-documented psychological and societal phenomenon. Throughout history, individuals who exhibit narcissistic, sociopathic, or authoritarian traits have managed to cultivate intense loyalty, even when overwhelming evidence exposes their corruption, deception, or cruelty. Understanding this attraction requires a deep dive into the psychological mechanisms that drive people to admire and defend deeply unethical yet charismatic leaders. History, psychology, and social structures all play a role in explaining this unsettling reality, revealing why people can remain devoted to figures whose actions contradict basic moral and ethical principles.

The Psychology Behind the Attraction to the Repugnant

From a psychological perspective, figures like Trump appeal to certain individuals due to a variety of factors, including perceived strength, charisma, and the projection of personal aspirations onto the leader. Many of his followers see in him a reflection of their grievances, frustrations, and desires for power, status, or revenge against perceived enemies (Hogan & Kaiser, 2005).

- The Appeal of the “Strongman” Persona

Psychologists argue that people who feel powerless or disenfranchised often gravitate toward figures who project dominance, defiance, and authority. Research on authoritarian personality theory (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950) suggests that individuals with high authoritarian tendencies are drawn to leaders who offer rigid worldviews and promise protection from external threats, whether real or manufactured (Altemeyer, 1996). Such individuals often seek strong leadership that provides them with a sense of stability, certainty, and security in a rapidly changing world.

This helps explain why Trump’s overt displays of aggression, insults, and divisive rhetoric resonate with certain groups. Many of his followers do not perceive these behaviours as flaws but rather as symbols of strength and defiance against an establishment they distrust (Mason, 2018; Napier & Jost, 2008). Research suggests that individuals who feel socially, economically, or politically marginalized are more likely to support leaders who exhibit authoritarian dominance and anti-establishment rhetoric, interpreting these traits as evidence of authenticity and resilience rather than unethical conduct.

A striking example of this occurred on February 28, 2025, during a meeting in the Oval Office, when President Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance publicly berated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, accusing him of ingratitude for U.S. aid and pressuring him to comply with American demands (New York Times, 2025). This public confrontation, broadcasted live, was intended to showcase Trump’s dominance on the global stage. However, while many international leaders and analysts viewed the incident as a diplomatic failure that weakened U.S. credibility and damaged alliances, Trump’s most ardent supporters perceived it as a demonstration of strength and control.

This disparity in perception highlights how those drawn to authoritarian figures may overlook, justify, or rationalize behaviors that others recognize as detrimental or embarrassing. Research suggests that individuals with strong authoritarian tendencies prioritize dominance and order over democratic norms, leading them to embrace humiliating and coercive tactics as legitimate displays of power (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). For them, Trump’s behavior was not seen as inappropriate but rather as a strategic move reinforcing his position as a leader unafraid to “put others in their place.”

By fostering a culture of humiliation, these leaders not only degrade their opposition but also reinforce a hierarchical worldview where power is maintained through coercion, not cooperation. For individuals drawn to authoritarianism, these displays satisfy a subconscious need for order and retribution, even when they come at the expense of democratic values.

Delving into Trump’s personal history provides additional context for these behaviours. Reports indicate that Trump’s father, Fred Trump, was emotionally abusive, described as a “high-functioning sociopath” (Trump, 2020). This environment likely deprived Donald of essential emotional nurturing, potentially leading to the development of narcissistic traits. Studies have shown that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as emotional abuse and neglect, are significant risk factors for the development of narcissistic personality disorder in adulthood (Cramer & Jones, 2023). Furthermore, research indicates that individuals exposed to such environments may develop maladaptive behaviours, including aggression and a lack of empathy, as coping mechanisms (van Schie et al., 2020).

Understanding these formative influences offers insight into how Trump’s upbringing may have shaped his interpersonal style, which, in turn, appeals to certain segments of the population seeking strong, defiant leadership.

- The Role of Charisma and Psychological Manipulation

Trump, like many other controversial leaders, possesses an innate ability to manipulate perception. Researchers studying Dark Triad personality traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—have noted that figures like Trump exploit these traits to command loyalty and manipulate public opinion (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

- Narcissism: Trump’s self-aggrandising behaviour, exaggerated achievements, and need for constant admiration create an illusion of supreme confidence and success, drawing in those who seek to associate themselves with perceived winners (Miller et al., 2019).

- Machiavellianism: His strategic use of deception, gaslighting, and manipulation enables him to reshape reality, making followers question facts and embrace his alternative narratives (Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, 2017).

- Psychopathy: His lack of empathy, impulsivity, and disregard for consequences make him fearless in attacking opponents, a quality that some followers admire as “toughness” or “authenticity” (Jonason, Webster, Schmitt, Li, & Crysel, 2012).

The Paradox of the Attraction to Abusers

Why do people, particularly those who have experienced marginalisation or rejection, align themselves with figures who embody cruelty and manipulation?

One explanation is that people unconsciously seek what is familiar, even when it is harmful. Research in attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) suggests that individuals who grew up in abusive, neglectful, or emotionally unpredictable environments often gravitate toward relationships that mirror those early experiences.

- People who equate safety with conflict, chaos, or control may subconsciously seek out leaders who embody those same traits (Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, & Holland, 2013).

- Those who feel rejected or excluded by mainstream society may latch onto figures who promise to “fight for them,” even if that fight is built on deception and manipulation (Federico, Fisher, & Deason, 2011).

This also helps explain why many people in abusive relationships defend their abusers—it is less about logic and more about deeply ingrained emotional conditioning (Crittenden & Dallos, 2009).

The Cult-Like Devotion to Corrupt Leaders

Political psychologist John Dean (2006) describes how authoritarian followers develop an almost cult-like loyalty to figures who validate their worldviews.

- Cognitive Dissonance: Once people have invested time, energy, and identity into a leader, admitting they were wrong becomes psychologically painful. Rather than confront reality, they double down on their support (Festinger, 1957).

- Us vs. Them Mentality: Figures like Trump create a binary worldview—you are either with him or against him. This triggers tribal loyalty, where followers remain committed out of fear of being ostracized (Van Prooijen, Krouwel, & Pollet, 2015).

- Repetition and Propaganda: Studies on political propaganda (O’Shaughnessy, 2004) show that constant exposure to misinformation, slogans, and repeated messaging creates emotional bonds stronger than facts.

This explains why Trump supporters often dismiss factual evidence of his corruption—it threatens their identity and sense of belonging more than the leader himself (Bartlett, 2018).

Breaking Free from the Cycle of Attraction to the Repugnant

How do we break the psychological grip that repugnant figures hold over their followers?

- Media Literacy & Critical Thinking – Educating people on how misinformation and psychological manipulation work can help them resist being deceived (Lewandowsky et al., 2017).

- Therapeutic Interventions – Many people drawn to abusive figures have unresolved childhood trauma. Therapy can help individuals recognize destructive patterns and develop healthier relationships (Siegel, 2012).

- Community and Belonging – If people find genuine connection and support elsewhere, they are less likely to seek validation through harmful affiliations (Putnam, 2000).

Breaking Free from Toxic Attachments

At Counselling and Psychotherapy Services for Men in Sydney,

Christian Acuña

helps individuals untangle toxic attachments, whether in politics, relationships, or personal identity.

If you find yourself struggling with loyalty to someone who has proven to be harmful, therapy can provide

the tools to redefine your values and cultivate genuine, healthy connections.

Take the First Step Towards Change

Book a confidential consultation today to begin your journey toward emotional freedom and self-awareness.

📍 Visit us: Contact Page

📩 Email: info@counsellingformen.com.au

📞 SMS: 0415 237 494

Final Thought

While intelligence and morality alone do not guarantee immunity from the pull of authoritarian figures, education, emotional security, and a strong sense of community act as protective factors. Figures like Trump thrive on division, misinformation, and emotional exploitation, but those with a broad worldview and critical awareness are less likely to fall into the psychological traps that fuel mass loyalty.

Understanding why people are drawn to such figures is not about condemning individuals who follow them but about addressing the root causes—unmet emotional needs, social disconnection, and unresolved trauma. By fostering critical thinking, emotional resilience, and strong social ties, individuals and communities can work toward resisting the pull of manipulative and destructive leaders.

If you or someone you know is struggling to break free from toxic loyalty, abusive relationships, or manipulative ideologies, seeking professional support can be the key to reclaiming autonomy and emotional well-being.

References

- Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. Harper & Row.

- Bernstein, C., & Woodward, B. (1974). All the President’s Men. Simon & Schuster.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

- Cramer, P., & Jones, C. J. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences leading to narcissistic personality disorder: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 17, Article 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-03714-3

- Dean, J. W. (2006). Conservatives Without Conscience. Viking Press.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. University of Chicago Press.

- Michigan Civil Rights Commission. (2017). The Flint water crisis: Systemic racism through the lens of Flint. State of Michigan Report. Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/mdcr

- Napier, J. L., & Jost, J. T. (2008). Why are conservatives happier than liberals? Psychological Science, 19(6), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02124.x

- New York Attorney General. (2019). Trump Foundation to dissolve after misuse of charity funds. NY State Attorney General’s Office Report. Retrieved from https://ag.ny.gov/press-releases/2019/trump-foundation-lawsuit-settlement

- O’Shaughnessy, N. J. (2004). Politics and propaganda: Weapons of mass seduction. Manchester University Press.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

- Trump, M. L. (2020). Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man. Simon & Schuster.

- van Schie, C. C., Jarman, H. L., Huxley, E., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2020). Narcissistic traits in young people: Understanding the role of parenting and maltreatment. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00121-1

- (2023). Personal and business legal affairs of Donald Trump. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_affairs_of_Donald_Trump

- The 19th News. (2023). The history of Donald Trump’s sexual assault allegations. Retrieved from https://19thnews.org

- The Guardian. (2023). The long list of legal cases against Donald Trump. Retrieved from https://theguardian.com

- The Atlantic. (2023). The Cases Against Trump: A Guide. Retrieved from https://theatlantic.com

- FindLaw Caselaw. (2023). CARROLL v. TRUMP. Retrieved from https://caselaw.findlaw.com

- Syracuse University News. (2023). What Happens to the Pending Criminal and Civil Cases Against Trump Following His Election? Retrieved from https://news.syr.edu

- State Court Report. (2023). Harvey Weinstein, Donald Trump, and Evidence of Past Misconduct. Retrieved from https://statecourtreport.org

- Crush The LSAT Exam. (2023). Donald Trump Settlement & Lawsuits – History of Legal Affairs. Retrieved from https://crushthelsatexam.com

- (2023). Trump avoids punishment at hush-money sentencing. Retrieved from https://reuters.com

- Business Insider. (2023). Donald Trump is serving a second presidential term. Here’s the lowdown on his personal life, career, and politics. Retrieved from https://businessinsider.com

- New York Magazine. (2023). Trump Sues Iowa Pollster Who Annoyed Him. Retrieved from https://nymag.com

- The Guardian. (2023). ‘He could go to jail’: for Donald Trump, election day is also judgment day. Retrieved from https://theguardian.com